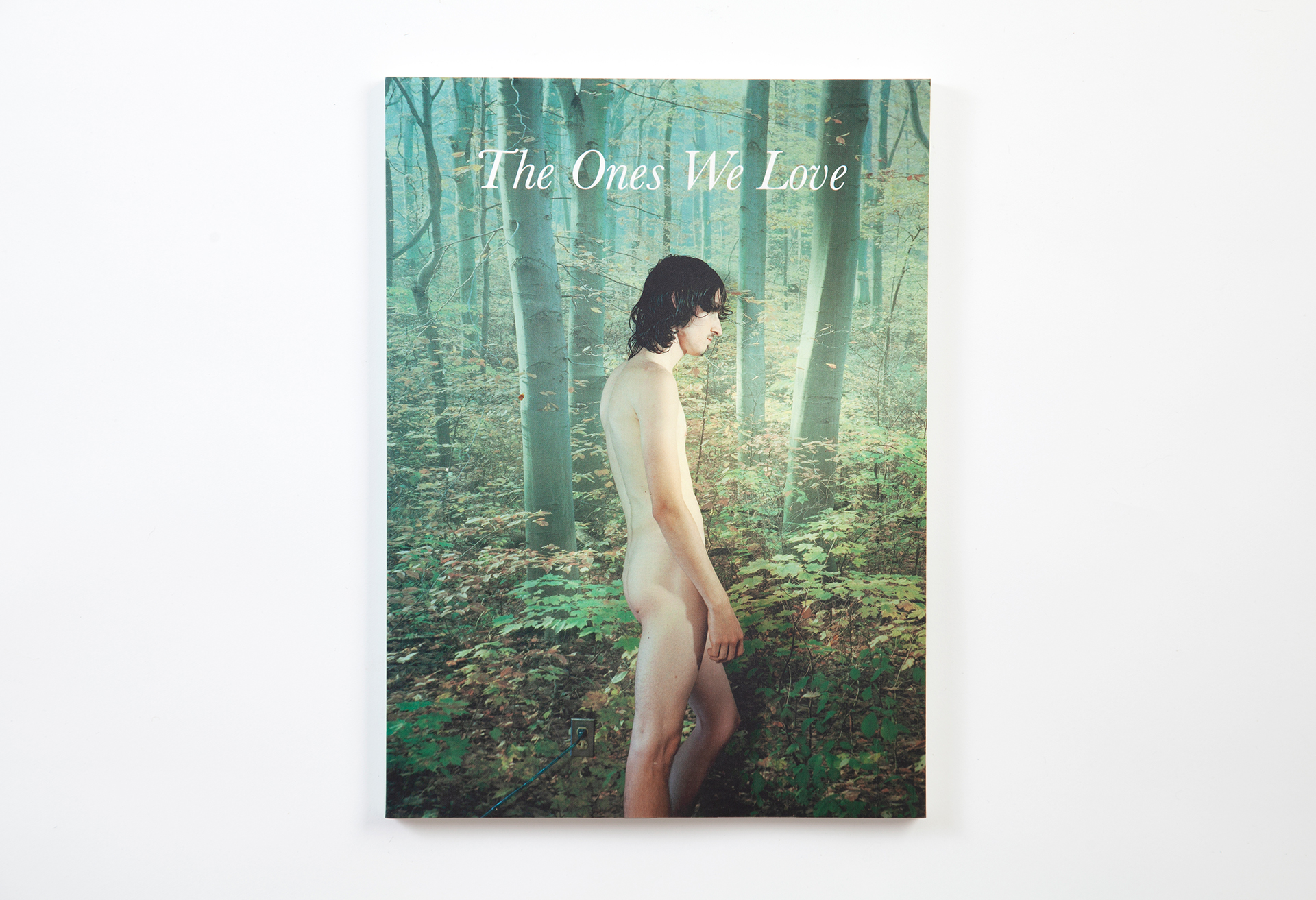

MICHAEL

Michael: FOREST KELLEY

Interviewed by Stuart Pilkington

Originally featured in The Ones We Love Issue No. 2. Iowa.

Life can be “horrible, horrible, horrible,” as Bertrand Russell once said and any one of us can get trapped in a situation. We can become physically or mentally unwell. We can become so unhappy that suicide seems like the only option. I hold no judgment on such a finite action. I remember seeing a documentary about Adam Ant, in which he described people who self-euthanize as “brave” as opposed to selfish. I understand what he was alluding to.

In an attempt to understand his uncle's death (possibly a suicide), Forest Kelley has used the medium of photography to explore his uncle's life in the series Michael. Thoughts and memories can be like gases, but when you write them down or transmute them into an image, you suddenly solidify them. It's a process that can allow you to make sense of something that is deeply personal and possibly difficult to comprehend. Indeed, before you make the set of images or put pen to paper, you aren't always aware of how you feel or what your thoughts are about your subject.

Forest is a highly accomplished image-maker. In Michael, one can see echoes of Philip-Lorca diCorcia's work, not only because the subject matter is of gay men, but also due to the use of color and light, the subject's facial expressions, and the framing with the use of windows and doors. Metaphor is cleverly incorporated into the series. For instance, there are many references to a divided self, such as a felled tree cut in half and a cracked rock below a picture of Jesus. There is also a strong cinematic quality to his work; you can see nods to stalwarts of the motion picture.

I decided to ask Forest some questions about his memories of his uncle and his own background. I found he was as erudite with his use of words as he is with his photography.

—

Stuart: I read that you were born in 1980, so that would have made you five when your uncle died. Do you have many strong or vivid memories of him?

Forest: I do have a few strong memories of Michael, but they are discrete and likely fallible as memories tend to be. Some are illustrated in my photographs, such as Michael on the Porch circa 1984. For a number of years, Michael lived in a one-room cabin without water or electricity on my parents' property. It was an unusual family proximity. I remember him drying off naked on our porch, reverently in the sun, after finishing a bath in our house. I remember him teaching me the Charleston dance where your hands cross your knees, creating the illusion that your legs are passing through each other. He left and I was convinced that my legs were switched. I can also see glimpses of his funeral. But I was too young to comprehend death—that it lasts forever. The emotional experience has more to do with the spectacle of the event than the permanence of loss. After he died, I grew up with his cabin just into the woods near my house. We called it “Michael's Cabin.” There was always an awareness of him in my life. Even in his absence.

Stuart: Do you feel a sense of honoring your uncle and solidifying his existence and experience by producing this series?

Forest: There is certainly a sense of honoring him in this work by reimagining, or reclaiming, a history that was obfuscated and tucked away. Shame and guilt around suicide, homosexuality, and AIDS in the 1980s was difficult for families to come to terms with—especially when there was so little room in the public conscience for these realities—and, of course, for many it still is. My generation is beginning to understand what we lost after AIDS. It was a time when family and friends mysteriously disappeared. It was a time of funerals and last suppers for young men. There is no context for understanding these events as a child. But as histories and contexts emerge, the vacuum is palpable. It's easy for Americans to comprehend the toll of war on our families and communities. By 1991, three times more Americans died of AIDS in the United States than in Vietnam. In 2008, before I started sincerely working on this project, I remember Chuck Mobley [SF Camerawork curator] saying, in a matter-of-fact tone, something to the effect of, “All of my heroes are dead.” I think it was in that moment that I felt what I had lost growing up in Michael's absence. With this project, I wanted more than to simply illustrate a history. I want it to be clear that I stand by queer history and that it has an influence on me. I have an amazing cassette tape of Michael chatting with a few friends. He talks about reading The Jungle, and how it was “so heavy.” The conversation is bookended by short clips from Lou Reed and then Chopin. I had so much to gain—at the end of a dirt road in a small rural town—by growing up in close proximity to an avant-garde, artist, intellectual, gay man.

Stuart: Was the act of exploring your uncle's life a therapeutic experience? For example, did it help you come to terms with his untimely death?

Forest: Of course. Making this work has answered a lot of questions and allowed me to grow in ways that I expect I might have if he had lived. The work is as much about the experience of making it as it is about art objects. By reenacting events, by talking with Michael's friends, and by participating in the culture that he was a part of, I think that I have come to know some facet of him. Or, at least, I was able to gain an understanding of the boundaries and possibilities. By visiting with his friend Greg (whose father was the notable painter Sante Graziani), I learned that Michael was a fan of Fassbinder and Fellini, for example. I also discovered that he was more interested in art than activism, and more “sprite” than depressive. These are tangible things. My sense of him as a person, and what he might have brought to my life, is now much more vivid. But, of course, it's not all fantasy. It didn't occur to me for quite some time that if Michael had not committed suicide, that I might have watched him die from AIDS. So once again, this figure that I have mythologized is gone.

Stuart: How has the rest of your family reacted to your dedication to him?

Forest: My parents have been supportive—particularly my mother. They were close with Michael; they let him live on their property. I would like to think it has also given those that I have talked with an opportunity to continue to process the meaning of his death. That being said, I've talked with a relatively small number of my extended family about this work. I have proceeded with caution. It may be a paradoxical thing to say, but I feel strongly that even those who contributed to a culture of homophobia, or even denounced his homosexuality, still loved him as family and as a friend. And I'm not sure that that made Michael's life easier.

Stuart: The story is in one sense biographical, but it also contains some artistic conjecture. Would you say that there is an autobiographical element to it, too?

Forest: What is true about this work is that it is a reflection of my imagination. The story that I am telling is very much a subjective one. I want the viewer to know that these works are not simply a window into one man's story, but that they are visions that sit in the imagination of the protagonist's nephew. Moreover, the work is autobiographical in the sense that as I remake this history, the process of researching and reenacting becomes a part of my own experience. These photographs are fictions, but they are also a record of me making them. I might say that the enactment of this work is an attempt to align our subjectivities and biographies.

Stuart: Did you consider leaving the images to speak for themselves or was it important for you to write some accompanying text?

Forest: I like to include text to help situate a viewer within the story. It can instigate the imagination as much as guide the read of the images. But still, this work is as much about what is unknowable as it is about the facts of a history. In that sense, the photographs should leave room for questions and interpretation. Myth is at least as important as evidence.

Stuart: Does the model/actor have a physical resemblance to your uncle and was that an important decision?

Forest: He does. I was working on the project for more than a year without knowing if I would find a way to represent Michael in it. I was invited to a three-day fortieth anniversary celebration for a community called Butterworth Farm, which was an inclusive back-to-the-land commune founded by five gay men in the 1970s. Michael visited from time to time. I found out about Butterworth in 2008 after I discovered a flyer inside Michael's trunk announcing their ten-year anniversary. Tragically, four of the founders contracted AIDS and had died by the early 1990s. However, it was, and still remains, a culturally rich and open environment, and I imagine that it was an important place of growth and acceptance for my uncle. A few days into the celebration I attended a party under an outdoor tent dubbed the Ruby Red Ball. I was wearing a red dress loaned to me by a friend of Butterworth when I was introduced to a young man in a paisley shirt and colorful bell-bottom pants who would eventually stand in for Michael. I learned that he was methodically listening to and cataloging chronologically the recorded history of psychedelic music from the 60s and 70s. I felt as if I were meeting my uncle in a time warp. It was serendipitous.

Stuart: I notice that in some of your other projects you use video or moving images. Do you consider yourself a visual artist or primarily a photographer?

Forest: My work and background is dominantly photographic, but I am not particularly interested in media specificity. There is something powerful in the assertion of truth that photographs, indexical media, and ephemeral objects have, and that's why I think I continue to love photography. But I am interested in a more dynamic experience of art.

Stuart: You also touch upon Christianity in your work. Is the relationship between religion and sexuality something that you want to continue to explore through your images?

Forest: Michael and I grew up in a community that is dominantly Catholic. I think that was something that Michael really struggled with: reconciling his sexuality with religion. That's quite a powerful rift, so I contend with that in this narrative. Another way of putting it would be to say that I'm trying to hold religion accountable for its role in homophobia—and, also, to point to its contradictions. Catholicism is homophobic but depictions of Jesus often dramatize femininity, for instance. But I don't think much about making work that contends with religion outside of this project.

Stuart: You have a great fluidity and looseness to your compositions. Is that instinctive?

Forest: That's flattering. In this series I do try to vary the compositions so that the narrative has a feeling of movement and vantage. I do this specifically because my intention is for most of the photographs to be read as subjective points-of-view rather than omniscient windows into a world. A degree of variation helps to assert that idea. But, there is still a vocabulary of composition; some compositional ideas I like to reiterate and others I work not to repeat. The majority of the photographs in this series are made with a large format camera and many are quite elaborately staged. I am interested in the photographs conveying an air of theater and, at the same time, feeling subjectively present.

Stuart: Which photographers influenced you in terms of style and content?

Forest: Michael was an artist. He studied painting and cinema at a community college and had a membership to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—quite a rare commitment for a young man from a rural, working-class family. I like to think about this project as somehow collaborative, and an extension of his own work, and so I try to derive as much influence from his interests as possible. I want the work to be as much an extension of Michael's vision as my own. Rainer Werner Fassbinder—the film director—is the foremost influence, as Michael was a fan. But, also, photographers such as James Bidgood and Nan Goldin who were making work in cultures that paralleled Michael's. I also draw from archives of photographs from queer culture in the 1970s and early 80s, particularly photographs from communities that Michael was a part of, such as Butterworth Farm.

Stuart: How has Michael's death shaped your view on suicide? Has it made you empathetic towards those people who attempt it and those that actually end their lives?

Forest: Suicide is hard to get past; it leaves the living with so many questions. A younger cousin of mine committed suicide just a few years ago. I can't help but wonder what a person was thinking in that moment. One can't help but weigh the entirety of someone's history against that finite event. A few months after Michael died our family received a hospital bill for a blood test addressed to him. This was not long after the HIV antibody test first became widely available. But it's unlikely that we'll ever know if his suicide was a means to avoid a scary death or if he was simply upset. My mother reminded me of how little was known about AIDS at that time. It's possible that he wanted to keep his family safe from what was then a mysterious disease. On the other hand, it's likely that he feared being outed, in a very public way, by the disease. It was one thing to be homosexual in that time and place; it was another to be branded by disease with a set of beliefs about your lifestyle. I'm not trying to imply a moral position on suicide, but empathy does call us to question the social conditions of it. A lot of gay men committed suicide in that time to escape more than disease.

—

Forest Kelley (b. 1980) received a BA in Social Economics from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. For the past three years, he has taught photography, digital art, and time-based media at institutions including Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Rochester, and Syracuse University. He is currently the Photography Fellow at the Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia.

Stuart Pilkington is a photographer and curator based in the UK. He has curated projects such as The 50 States Project andThe Swap which have featured on the BBC, Esquire and National Public Radio. In 2015, he set up the first Pilkington Prize, a landscape competition called '100 Mile Radius.' He has photographed film directors such as Terry Gilliam, Alan Parker and Luc Besson for the British Film Institute.