MICHAEL

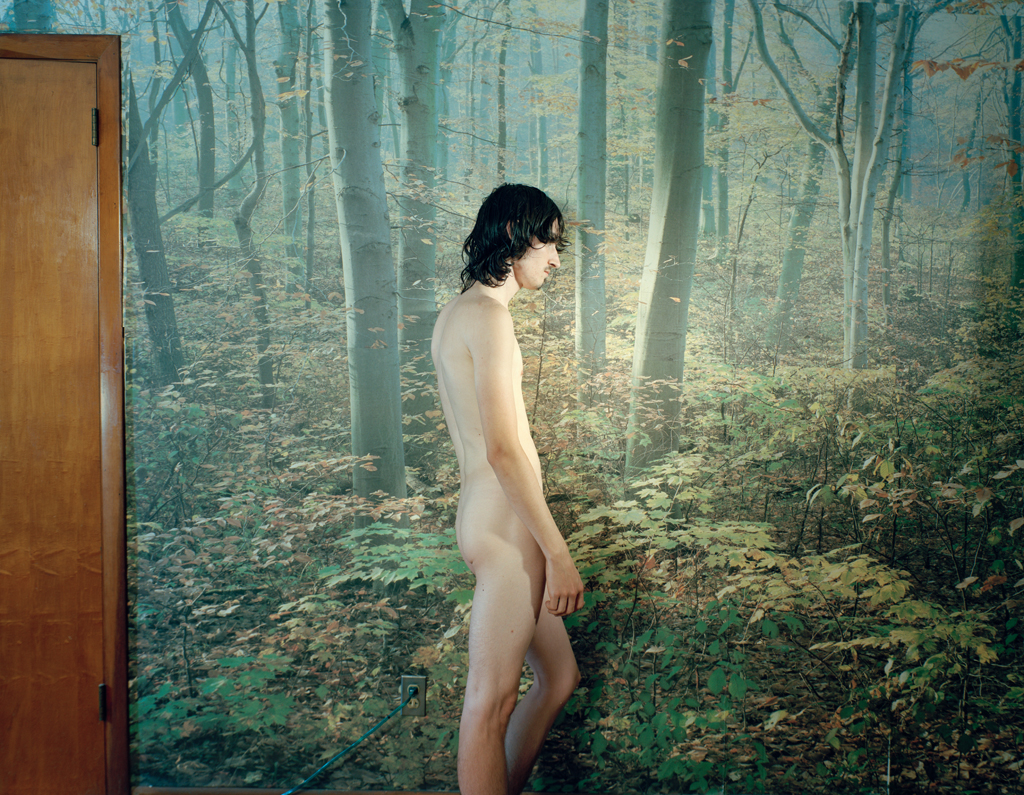

This project imagines the history of gay men living in rural New England in the era between the Stonewall Uprising in 1969 and the death of Rock Hudson by AIDS in 1985. Specifically, I trace the experiences of my uncle Michael, an artist whose adult life was bookended by these landmark events in queer history. Michael was found dead at the bottom of a cliff—a presumed suicide—on June 14, 1985, shortly after the first test for HIV antibody was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration.

When a person dies, that loss ripples through many communities and is felt keenly by many people. My life would have been different had Michael lived; his very absence has been formative. My work connects me to a past that was and a present that could have been.

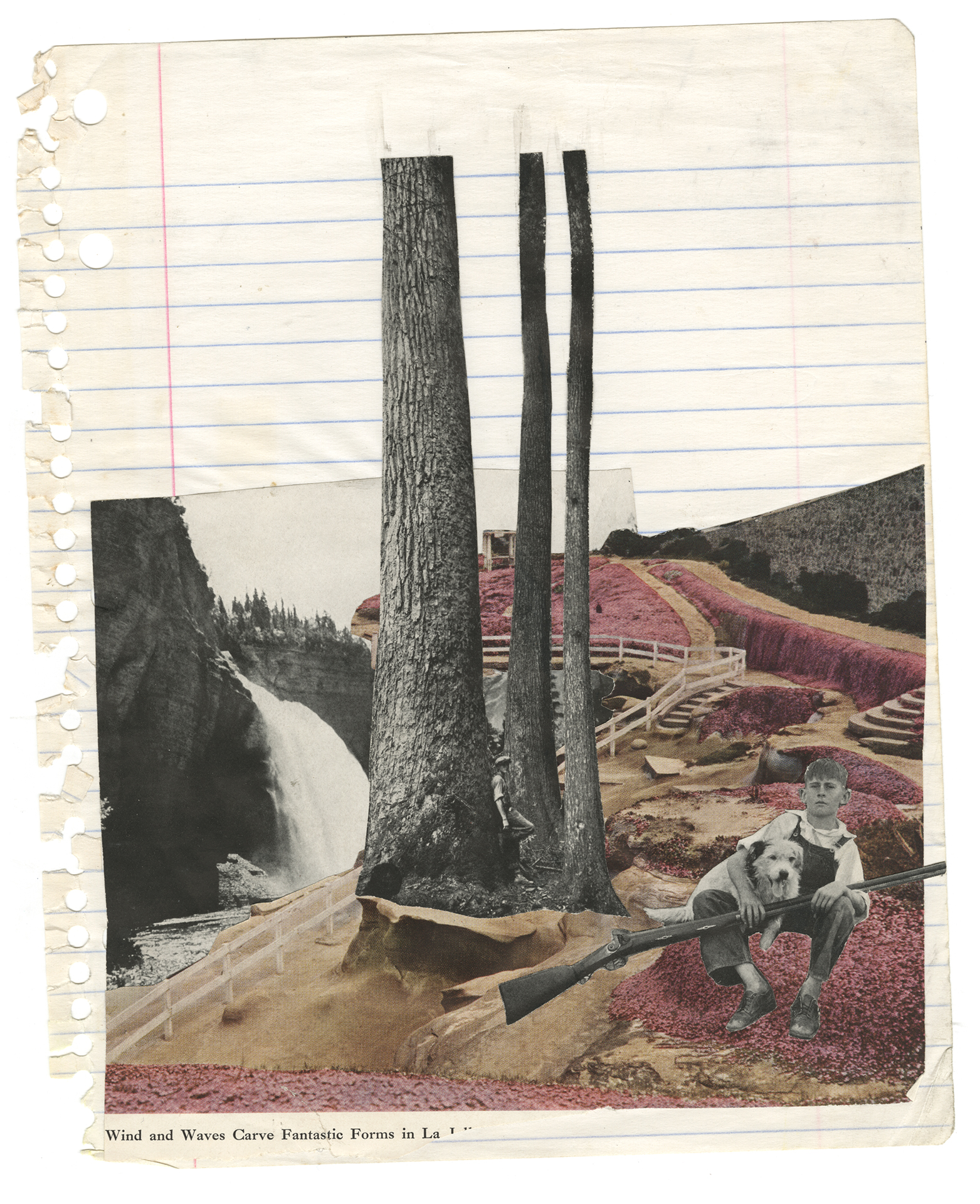

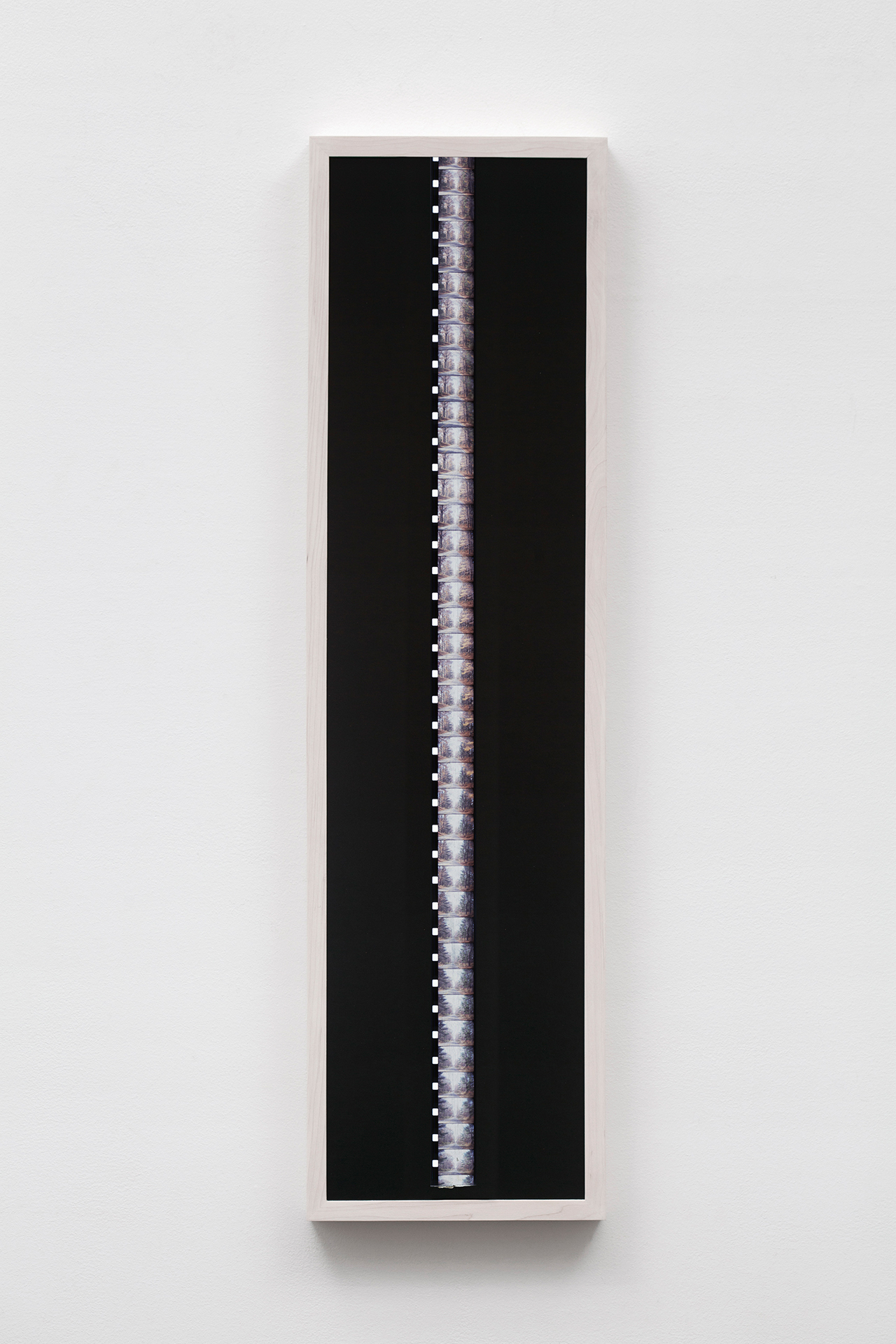

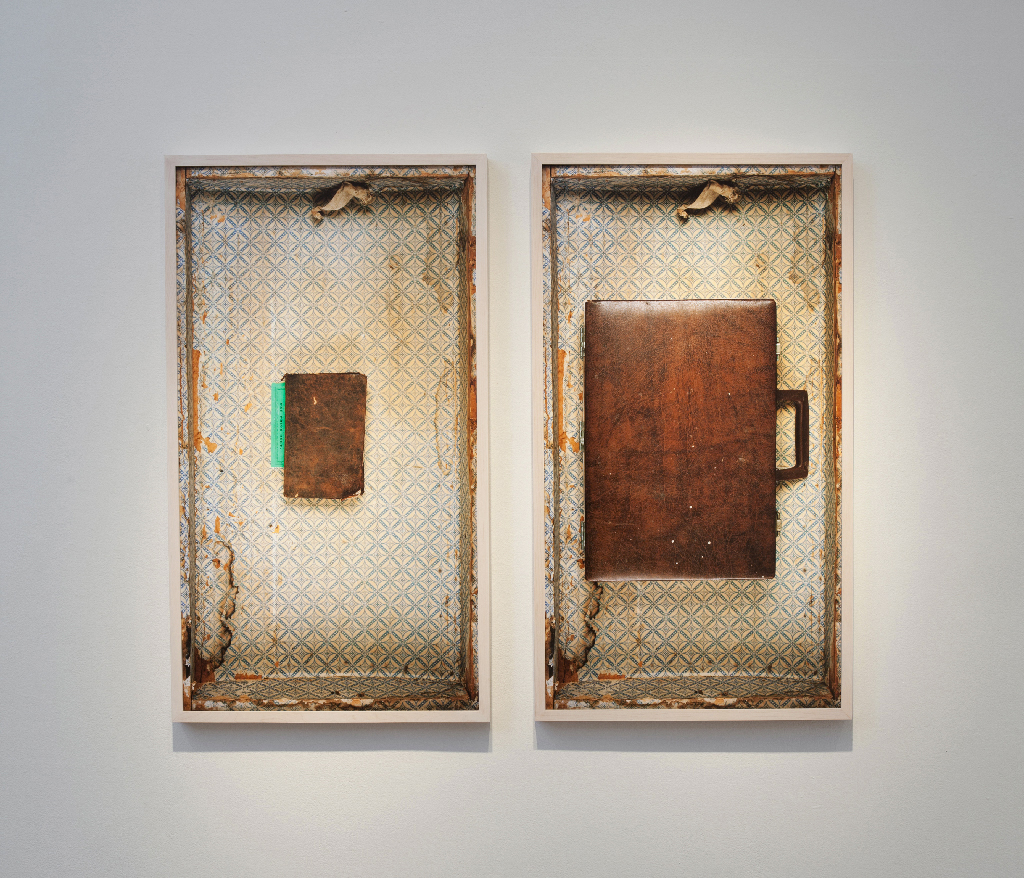

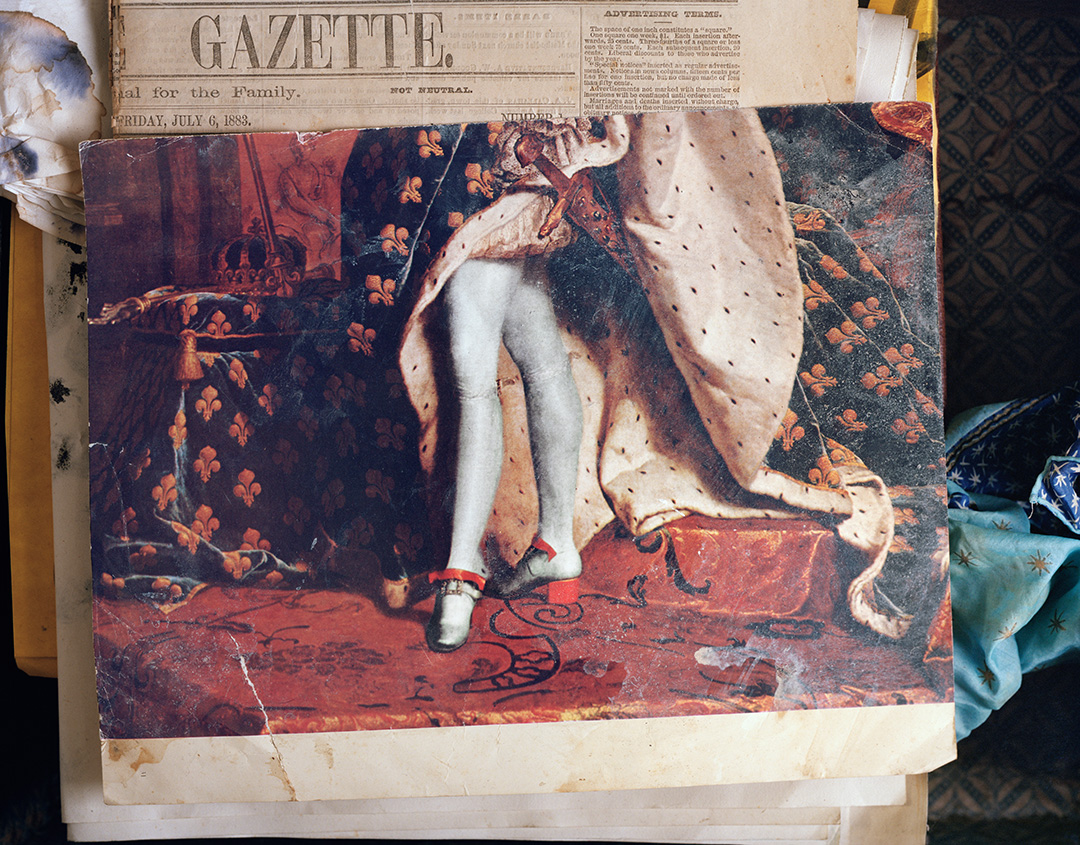

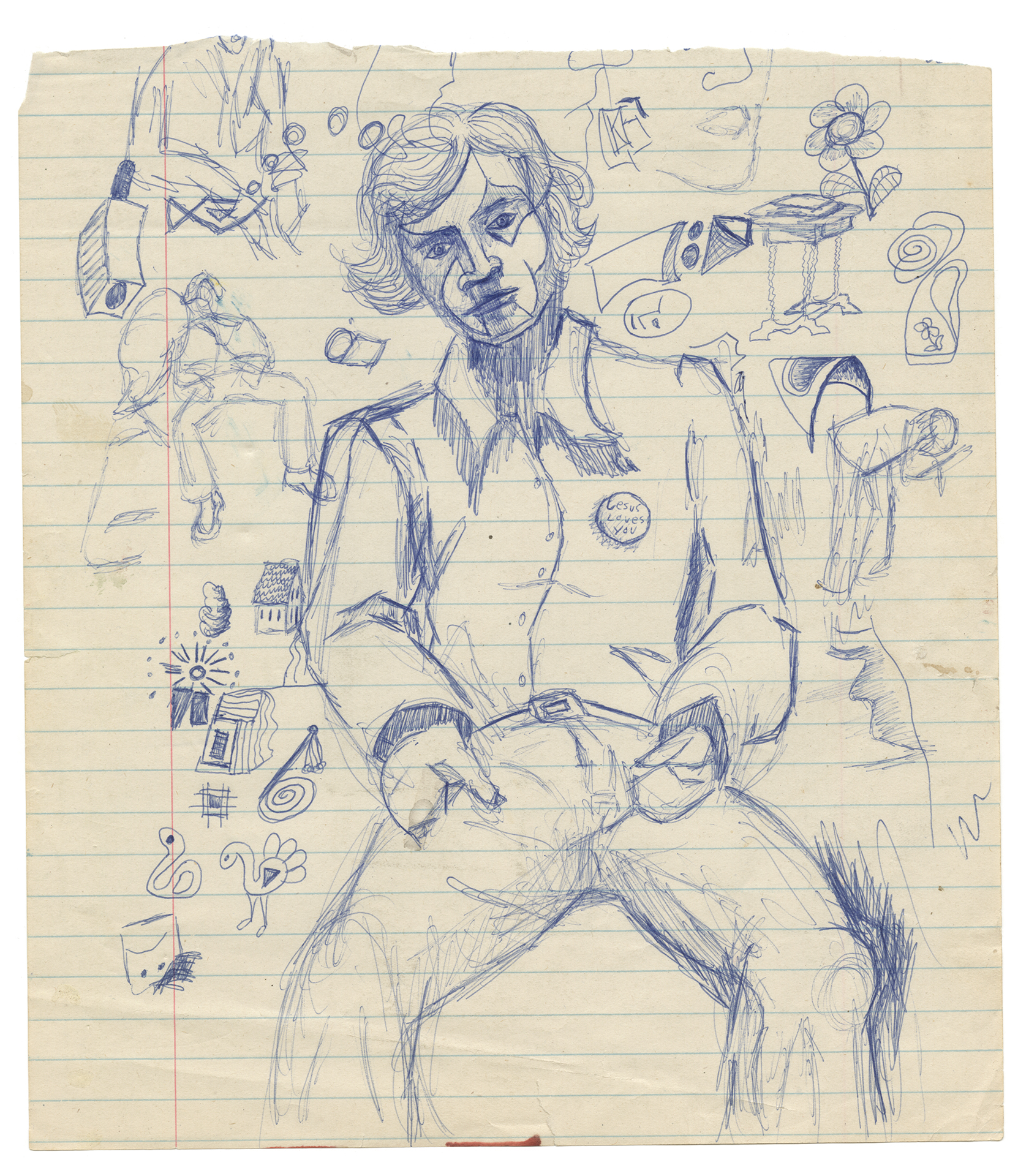

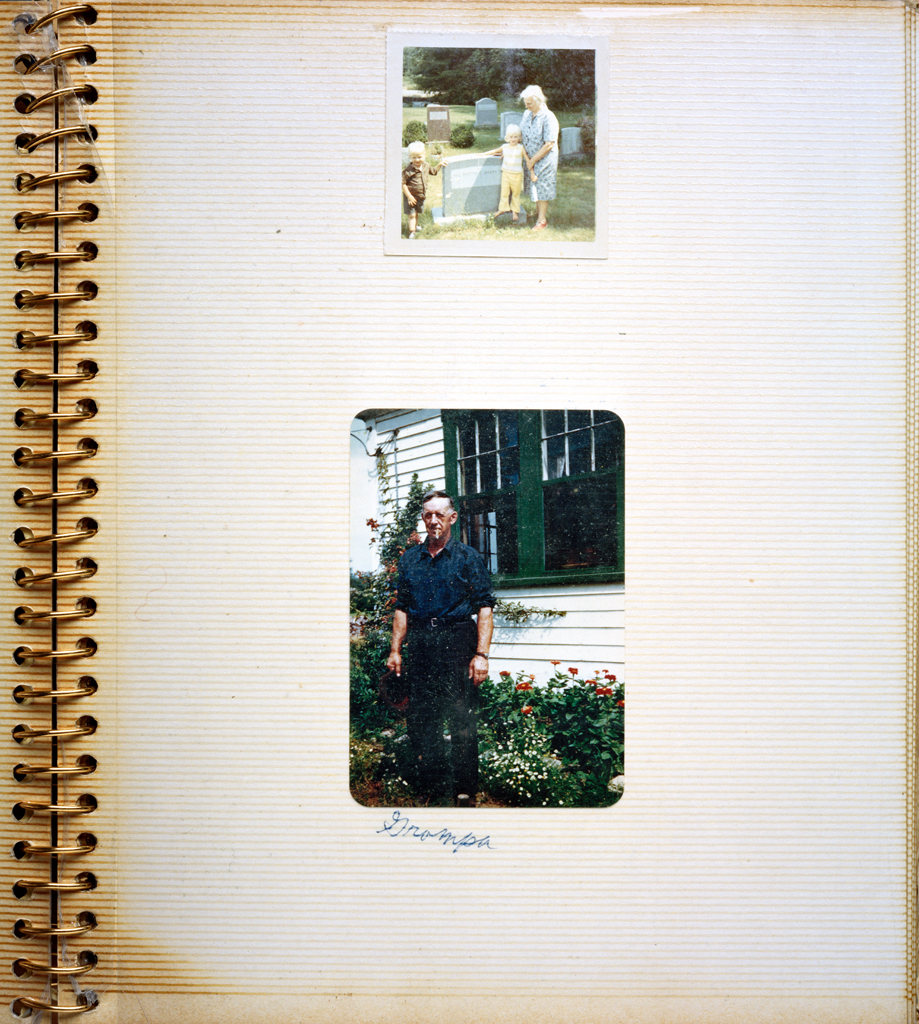

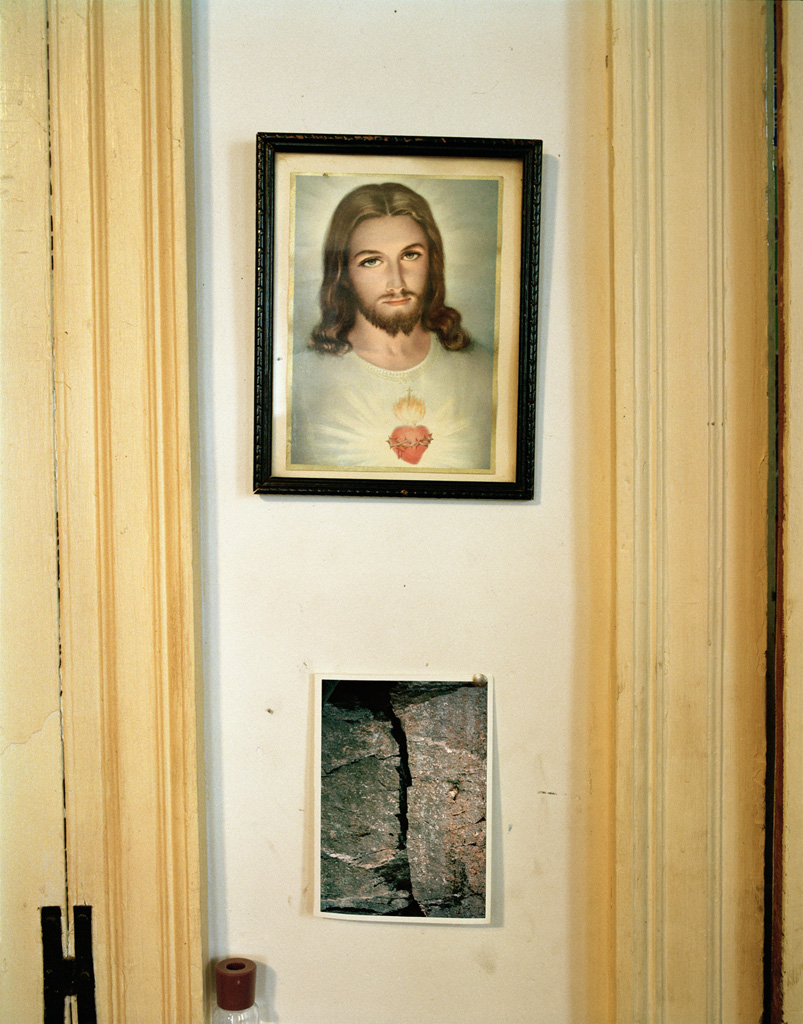

My photographs reenact known events and memories, reconstruct shared histories, and speculate on experiences Michael might have had. The project also incorporates and interprets ephemera—the things he left behind when he died—and his own 8mm filmstrips. Using Michael's own possessions and work allows me to materialize him and lets him speak for himself, grounding my imagined images.

Part documentary, this work seeks answers. But its preoccupation is with the unknowable, with visualizing the hopes and fears that continue to resonate within our family and community. Quieted and forgotten histories become exiled truths. This work is an attempt to resurrect one of those stories.

Robin (Michael's sister-in-law): It's funny, because that was the thing that was just going through my head. We're going to go down the path, the last path that Michael took down the road [long pause] before he died. You and Erin and Floyd were following him. Suzette was over and we realized you children were missing, and were like, "Oh my god." We came and got you. Michael carried Floyd in his arms, back. I wish I had written down what Floyd was saying, but Floyd was yelling, “I have to go with Michael. I have to go with him.” I was like, “No, you can't.” Then we just stood down here, all of us, and watched Michael walk down the road.

Robin: You figure, it's kind of hard. Barre was only a town of about three thousand people. It's now almost six. But then, no cars went through the neighborhood. There was no traffic. So here you are, a gay kid where it's just farmers and the good ol' boys. The flag is a Budweiser symbol, you know? So what does a kid like that do? He knows he's different, something is wrong with him, and there is no one to talk to and no one to explain it to you.

detail

Dear John, Allen, Buddy, and Dennis,

Thank you for the wonderful and pleasant week I spent with you people. I think I learned a little bit about Eden. Also, the party was a real good time and the reefer was fine. See you in the future.

Love,

Michael Kelley

Cynthia (Michael's friend. Email.): I loved your uncle. I thought of him as a poet. He struck me as ethereal and lovely. We knew he was gay and this must have been very difficult for him coming from such a small farming community. Also, at the time, mid-seventies, coming out wasn't that popular. I know he was delighted to find the Butterworth Road folks. I believe he was finding himself with their help.

I was living in New York City at the time of Michael's death and was shocked to say the least. I never believed his death was a suicide. I thought he had probably been high and took a missed step, purely accidental. Who knows? From what little memory I have of that time I never remember Michael as being depressed, just the opposite. I remember a sunny and joyful man.

In my mind's eye I see him as dancing a happy dance down the road.

I can't remember which classes we were in except painting, but I'm sure we were in several together. The art department was very small and us artist types hung together. Your uncle was highly creative, making small somewhat eccentric art, and writing poetry.

Forest: Do you think that would have been hard for him: to be a gay man in Barre?

Ted (Michael's brother): Oh, I don't know. I don't know. Probably not. You know, he was...

FK: Pretty comfortable?

TK: But, people can be mean. You know? And back in them days, yeah, more so than now. People can be, probably, against him. There are some people...

FK: You mean harass him?

TK: Yeah, beat him up, or go to gay bars and beat him up. There are people who would beat up people. They're out there. Not me.

detail

Greg (Michael's friend): The Factory. You see, Michael Kelley, he would have been the type of person that could just ooze in, so comfortably with those people, no matter how famous Andy was, or whatever, or how eccentric. I would probably have a hard time. I would have to be introduced properly, and all that sort of thing. I'd be more formal about it, and I'd be too shy to ask to do whatever they were doing. But Mike would be the type that would ooze right in.

Noreen (Michael's cousin. Daughter of John.): The Jehovah's Witnesses, when they'd come to my house, I'd still be sleeping. Because he used to sleep there, sometimes.

Johanna G (Michael's cousin. Daughter of Noreen.): Michael loved that.

NH: So Michael would entertain the Jehovah's Witnesses.

JG: He loved to talk to them.

NH: Forest Fessenden's mother, Esther Bacon, she couldn't believe it. Because the girl that used to come was kind of a young girl. Not bad looking. She had three boys. She was telling Michael you can pray in any position. It doesn't matter what position. You can pray in any position. And he goes, “Even the missionary position?" [laughs] So they were all upset, “How can you say that to sister Dada.”

The artist is content for himself

Feeling low for pushing out friends

Whyl letting them in to show I'm a kindly friend

Or wasting time only to cure my lust

Oh, oh, oh,

What can I do

To stop the love that

Betrays out of fear for myself?

The rubbing the lotion of life all over my face

Then facing the world and smiling

And thinking they might try to gas me

Ah paranoia sweat schizophrenia

Living lonely while trying to be

— Michael

detail

detail

Cynthia (email to Allen Young of Butterworth Farm): I did know Michael, I remember a beautiful and handsome man, tall, thin, black hair. We met at Mount Wachusett Community College, both of us in the art course. He was wildly talented, a deep thinker, with a good sense of humor. I loved his style. Always wearing fabulous outfits, colorful and exciting. I remember him as well as I can remember anything nowadays, and have thought of him often through the years.

I believe Michael would have gone on to greatness in the art world, had things been different. A real tragedy, that he went so young. I hope Forest understands how special and profound his uncle was for being so young, a great guy.

—

Ted: He had some mold in his eye, or something. He went to get checked out in Boston and then my mother might have scheduled art museums to go to because she wanted to get him to see the stuff before he goes blind. So she took him and left the rest. We didn't get to go to some of the art trips that he went on because she was afraid he was going to be blind.

Forest: How old was he then?

TK: Twelve or something.... It became a mission for a little while.

Greg: Here is another Michael thing. He would have known of that type of... classical males.... He would have known all about castratos and Shakespearean theater. You see, women, traditionally, weren't allowed to do the female acting, so they used, traditionally—even in Japan, or even Western European theater, women weren't actors. Men had to do the female parts, ironically, or were doing the female parts. In opera—it went back to ancient times—castratos were chopping off men's balls. It went way back to biblical times.

Forest: Did Mary and Bob know that he was gay?

Noreen: He came out of the closet and told them because some guy in Boston convinced him to, or somebody convinced him to tell, and he was sorry that he did. He wished that he never had, you know? Because Bob didn't treat him nice after that, I guess. In fact, I think Mary Kelley used to threaten to leave Bob if he said anything. That's how bad he must have treated him.

—

Robin: He called home one night—Mary Kelley's—and he had a boyfriend named Toby that was from the Cape. I think Toby talked him into it, saying, “You've got to tell the family.” And Toby is the one that helped Michael come out. He called his mom. Mary Kelley came into the living room and she—tsss. It was like, “what is the matter Mary?” She goes, “Michael just told me he's gay.” I'm like, “Really, he just told you?” “You knew?" [said Mary.] I went, “Everybody Knows. [laughs] Everybody knows Michael is gay.” She was just shocked by it.

—

FK: I heard that at some point he called your mother and came out to her.

Ted: Yup, yup.

FK: What did you think about that? You all knew he was gay right?

TK: It didn't bother me at all, really. I didn't have an issue with it.

FK: But did he even need to come out to you?

TK: No. Well, probably. Probably, yeah.

FK: Because nobody assumed that he was gay before then?

TK: Not really. You wouldn't label him. I wouldn't. No, I guess I wouldn't.

detail

Mark (Michael's friend, “The San Francisco Sissy.” Excerpt from a letter dated February 14, 1978.): You don't really know what your missin out here from your aspect of life. Just last night my best friend here now... is a 27 year old, black guy, I work at the bank with, a real nice guy. Last night me and him were in the (toilet) smoking a joint and he told me he's gay.

Ted: Supposedly, he was out there in the steam baths for men. In the bathhouses living, maybe, the gay lifestyle out there.... And for some reason my mother just didn't get a good feeling about when he was out there. As if they were treating him more rotten, or something.

Greg: What did you do in Barre? You went to Worcester. [What did you do in Worcester? You went to Boston.] And sometimes the joke went on to: what did you do in Boston? You went to New York. [laughs] That was, [pause] sort of, a joke.

Greg: Larry went to Boston a few times and did things like—remember how you were talking about the bathhouse in Providence? I did it a few times but it wasn't my thing. I didn't like it. It was too weird and too dark, and I didn't like to meet people like that. I'd rather be drunk and have good conversation, maybe, or meet people slowly. But, a lot of people did it. Sometimes, it was extremely promiscuous. And that was not a good thing that people were doing. So, maybe, I was lucky that way. That I wasn't, maybe. I don't know if you can blame it on promiscuity, or what, or luck, or whatever? You can't really say. But that's the story on that.

—

GG: At Copley Square, in front of the old fashioned part of the library there's a camera—me probably a little dot in the background—then, out of the corner of my eye, I'm looking at Larry and Patrick with my mother's car door open, and I think they were having sex they were so drunk. [laughs] That takes me back. So you don't do that anymore.

Forest: What was the camera there?

GG: Yes, there was. The channel five news. It was in the early evening. So here's channel five news, talking about some situation, interviewing, and I know I was probably in the background. Then, in the corner of my eye, I'm looking down whatever street that is behind the library, with my mother's car door open and four legs hanging out of it. It was awful. I'm sure we were buzzed enough not to give a damn. But still, that was one of those instances you never forget. The guy, Patrick—I don't know whatever happened to him—but he was like Patrick Von Wheatnow, I think his name was. He was like a Count. But he was telling me how that means absolutely nothing, you know? It really doesn't. He was a nice guy. So I had him and then Larry had him.

FK: The same night?

GG: No. I had him the night before. [laughs]

Forest: When do you think you got infected?

Greg: I'm guessing that it was either the late eighties or the early nineties because I had a really good relationship in 1989 with my best friend Ed. The big guy from Connecticut, from New London, and who died about three years ago—probably around this time of year. That entire year was very monogamous, except for, maybe, I had for ten years, or so, one of my best friends was in Barre that I saw. The butchest guy in town. [laughs] So we had a, sort of, secret affair, [laughs] but most gay guys don't have an affair like that. This guy was solid muscle, redneck from the foundry. You could tell, you know? The butchest guy in town, with a motorcycle. That's all I'll say. [laughs] You could tell how butch he was. One of my friends used to have a room at the hotel that was wonderful, actually. I can remember sitting on the balcony of the hotel. He was on the North Common. You could tell it was him just by the way he walked.

—

GG: So within four years, the famous cocktail was invented, which was mostly half AZT and half, whatever. It was very hard psychologically because every time you go shopping for a shirt you'd say, “this is the shirt that I'm going to be buried in.”

There will come a time when

There will be no one left

To expect to visit

Me

— Michael

Forest: Do you ever remember talking with Michael about AIDS?

Greg: We must have. Everyone did when it was starting to be discussed.

FK: What were people talking about?

GG: There must have been some wonder about the rarity of it. Because, you know, in real life, you didn't hear of anyone that you might have known actually dying back then. I remember Terry using the word—a lot of people would have to have been carriers that could live with the virus for a long time. That may have been a case that was happening to a lot of people. Having something and not really knowing it. Just like today. A lot of people have hepatitis and don't know it.

Robin: And we didn't even find out about all the other people in his life, and our lives, until a year or two after he even passed away, you know? So it was like, holy mackerel, they've all got AIDS.

Forest: Maybe it wasn't depression. Maybe it was just knowing a certain fate?

Robin: Yeah. Yeah, at that time, there was still a lot of ignorance, "Oh, can I get it off the water glass, off their toothbrush." It sounds stupid today, but that's just how it was. "Can I get it from breathing the same air in the room." People just, really, did not have true answers. And that information really was not out there because there was a lot of guesswork going on. So here he is, not really knowing the real answers, and he's thinking, maybe, to himself—this is all speculation—look at all these people I have interaction with, and maybe I've infected these people that I love. That's a lot for a mind to be able to deal with.

John (Michael's uncle. Noreen's father.): Twice I had dreams of being on a cliff and falling, falling, starting to fall and grabbing a branch, hanging onto the branch to save myself and the branch pulled out and it dropped down, a long way down. It happened twice, and I told my bookkeeper about it wondering what it meant. Then, two or three months later, Michael fell. I know that's what happened, that he didn't try to commit suicide or nothing.

Noreen: That's what Michael Ryder, the Chief, said, too.

JH: Michael Ryder said he was falling and he grabbed a branch trying to hang on to save himself and it pulled out of the ground. That's what happened. Just what I saw in the dream.

Forest: In your dream, do you remember hitting the ground?

JH: No, just falling, falling.

NH: Didn't you say everything went dark?

JH: Dark. Yeah. Falling into the dark. Yeah. Then I knew what happened. So I knew he was trying to save himself. He wasn't trying to commit suicide or nothing. Then when the guy said—the one in charge of that—said it was suicide, I tried to find him, where he lived. I went to his house and everything, and nobody was there, to tell him what happened really happened. But that's what really happened. He was on the edge, praying or something, to God, like. Then he slipped and fell.

FK: Does that make you feel better knowing that he didn't—that he tried to...

JH: Yeah. Well, yeah. Yeah.

Ted: She was going to give him ten dollars, and then John, at the time, didn't need him working at the farm because he had Helen there, and different people. So he gave Michael heck for wanting ten dollars because he knew at the same time that he cosigned on Michael's [car] loan, and now Michael doesn't have a job, and then he's bumming money off my grandmother. So he hollered at Michael, at that. And then Michael went out the door and said, “Some people are put on this Earth to work, and some people are put on this Earth to create works of art."

Robin: I said, “We'd better check, you know?” None of the friends had heard from him and none of them knew anything. After I had exhausted the list, it was like, "Oh, my God." So, Teddy and Gram went to all the special spots—Rice Ledges being one of them. Gram was up top and there was a flannel shirt all folded up there. She goes, “ I don't think this is Michael's.” And Teddy goes, “It's Michael's mom, because Michael is down here.”

Robin: She always blamed herself. She always kept thinking it was her fault, she did something. And no matter how much documentation and research you would bring her—and stuff she would even look up—she just could not believe that it wasn't her fault.

Ted: And then his car was there.... But I didn't really like his car being there because, when I would look at his car, I would feel like, “Oh, Michael's safe” because... if you saw his car there you'd know he made it home, and you could feel he was safe. After that, it kinda bugged me, his car being there.

Robin: Out of all the gay friends in that whole group. The only one that I know of that's alive is Greg. He's the only one. The last one left. Everybody else died. Michael killed himself. Larry, his whole body just gave up on him. He kept having operations. They removed this, they removed that. His immune system broke down. It was really devastating to see these people all die.

Ted: I don't think I associated it with that until afterwards. That thing came in the mail months afterwards.

Forest: And that's when you were like, “Oh...

TK: That could have been part of it. Or the idea that he could have had AIDS.

—

Robin: He had such a spirit for adventure. Nothing ever bothered him to go do. He never worried that he didn't have stuff. Having stuff wasn't an important thing. When we got the land from Grammy, Teddy said, “Well, what about Michael. There's no land left for Michael.” So Teddy went and asked Michael, “Michael, Mummy is giving me all this land, but that doesn't leave anything for you. Do you want some of the land?” Michael said no, he didn't have any interest... he just wanted a little cabin. If he could get him a little cabin to live in on the property, he'd be fine with that. So we went and got that cabin for a cord of wood and put it out in the woods there.

Greg: No. Mike was comfortable with his self. I think. You know? So there was no, "Oh no, what if someone finds out I'm gay," or "What if someone finds out I'm HIV positive," or something. No. That wouldn't have been in the question, I don't think. Because, one thing about his personality was he was comfortable about walking down the street and doing a twirl. You know?

Robin: You went outside without anyone telling you to. You remind me the most of Michael because you just have this sensitivity for things. Michael always had this unique sensitivity—and not because he was gay, but just very sensitive to things. You went out and the whole yard just bloomed with white daisies. You couldn't even walk in the yard. There were so many white daisies that just popped open. I've never had that since in the yard. And it was like, wow. Just symbols. But you went out and you picked this beautiful bouquet of wildflowers and brought it in and took it up to the funeral parlor and you put them in his casket.